Trained on our most intimate data, the next generation of AI models will be deeply personal. Modem collaborated with Chanwoo Lee, HCI designer at the Royal College of Art, to explore how our identities evolve when lifelike simulations begin to communicate on our behalf. Digital Doubles imagines a future where our avatars become agents—extending our virtual presence into the uncanny valley and beyond.

You may not know it, but you have a twin. This invisible double lives in your pocket, silently surveying every purchase and post, logging your private and public interactions with the cloud. It’s the “you” in For You Page: a homunculus of accumulated attention. It is to this twin, not you, that the social media platforms tailor their advertisements and influence campaigns.

As Douglas Coupland puts it in The Extreme Self, this “dematerialized parallel” is neither good nor evil, neutral or chaotic: it’s just “machines telling other machines that you recently purchased a piqué-knit polo shirt in tones flattering to your skin at Abercrombie & Fitch.” That is to say, consumer behaviors, even in the aggregate, don’t paint a realistic portrait of a person—at best, they form a garish caricature of who we are.

But this stands to change as small, powerful, on-device AI becomes more efficient and powerful. Trained on our data, behaviors, and tastes, the next generation of AI models will be highly personalized. Already, Google Assistant can make phone calls on its users’ behalf using a realistic generated voice—complete with “ums” and pause breaks. And using apps like Captions and BIGVU, content creators can generate AI twins to help them produce social media videos.

Extrapolated, this technology is poised to transform the fragmentary shadow selves into something far more uncanny: robust “digital doubles” capable of interacting with the world on our behalf. In the name of productivity, these avatar-agents might soon manage our daily tasks, present themselves convincingly to others in our stead, and even anticipate our future actions. Are we ready to meet our doubles—and do we even want to?

THE AUGMENTED SELF

It’s a productive day for the CEO and his digital doubles. CEO KeithPrime reads the surf report with his morning paste of sea moss and reishi. He has standup meetings in five time zones today but none are serious enough to warrant his presence—his doubles can speak for him. The ocean looks good: strong swells, temperatures below 80, bacteria levels tolerable. As KeithPrimes closes the surf cam, Keith2 pings him with some mockups: generated images of himself in the boardroom. He picks one where he looks tired and slightly unkempt, the sign of a hard-working founder. Nobody wants to see him glowing from his days on the beach. He chooses a healthier-looking alt to reskin Keith3, his dating profile. A few waves before noon. Enough time for the doubles to get him a lunch date.

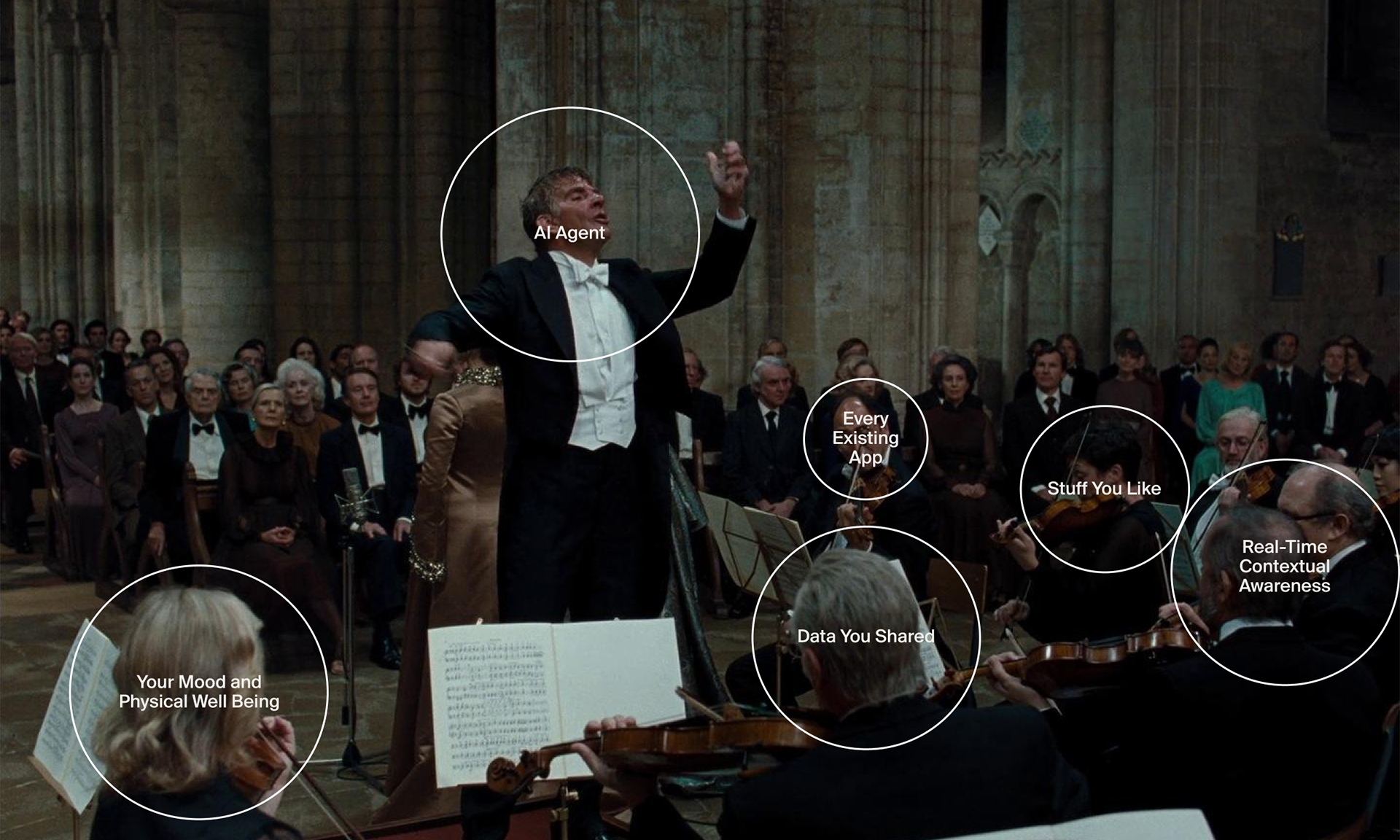

The notion that AI must be given unfettered access to our intimate lives in order to become truly useful to us is already being acted upon across Silicon Valley. Technology companies are rushing to build AI into their offerings at a system level, where they can train on our personal data and act on our daily lives. The Windows 11 operating system comes with Recall, an AI tool with a “photographic memory” of the snapshots it regularly takes of its user’s desktop. And in 2025, Apple will launch Apple Intelligence, an on-device AI that will draw from personal emails, texts, and photos to help users write better emails and “get things done effortlessly.”

The promise of these technologies is that they will automate away the mundane busywork of answering emails, responding to texts, sorting through photos, and scheduling meetings. Someday, according to Zoom CEO Eric Yuan, digital doubles may even attend meetings on our behalf, leaving their human counterparts to tackle higher-value creative work. Whitney Wolfe Herd, the founder of Bumble, promises something similar for dating, with AI “concierges” vetting romantic matches on users’ behalf. “Then you don’t have to talk to 600 people,” she explains. “It will scan all of San Francisco for you and say, these are the 3 people you really ought to meet.”

What Yuan, Herd, and other tech industry optimists propose is a world in which digital doubles sweat the small stuff so that we can be present for bigger, more important things. But their seemingly contradictory predictions beg the question: in the future, will we automate work in order to focus on our personal lives, or will we automate our personal lives so that we can spend more at work? The promise of simultaneous productivity and leisure is how automation has been sold to us since the days of the Jacquard Loom. But we can never escape work. Just as programming computers supplanted manual calculation, or maintaining industrial machinery replaced craft, managing our doubles may well become a new form of labor. At the same time, the normalization of enhanced productivity may only accelerate a race to produce more and more content—to be effectively everywhere all at once.

Further, if we relegate posting, work meetings, and bad dates exclusively to our digital doubles, how long will it take for our virtual and real identities to drift apart? As Marshall McLuhan once observed, every extension is an amputation. Just as our ability to write by hand, read maps, and memorize information has atrophied alongside the rise of keyboards and dictation, GPS navigation, and the Web, we may eventually cede small talk, writing, decision-making and critical reading to our doppelgängers—at our peril.

THE PERCEIVED SELF

Rikki just received a video call from her wife, Leila, who is in Dubai for a biotech conference. Before that it was Shanghai to close a deal, and before that Tanzania. The company is always sending Leila somewhere new. In fact it’s been months since she’s been home at all. Rikki jokes: you might as well be a double. Remember when you went to Costa Rica last March, when that freak hurricane wiped out the coast? Maybe it wiped you out, too. It’d be a lot cheaper for the company to pay for a double than a pension. haha, the Leila onscreen says, too quickly.

For the time being, our digital doubles sit squarely in the uncanny valley. Although social media is already flooded with deepfakes, bots, and AI-generated imagery, it’s still possible for discerning viewers to distinguish between real and generated content. But this critical capacity is unevenly distributed—as anyone with overly credulous parents or grandparents on Facebook knows—and its window of usefulness is closing. Soon it will be impossible to distinguish between a human and their digital agent, or agents, throwing nearly all online interactions further into a miasma of deniability and distrust.

Of course, if the popularity of dating simulators and AI girlfriends is any indication, it’s likely that many users, content with their strictly virtual relationships, won’t care. In some cases, the verisimilitude of a bot might be its primary objective. Eugenia Kuyda, the founder of the AI chatbot app Replika, was initially motivated to build her product by the death of a close friend, Roman Mazurenko. Trained on a corpus of Mazurenko’s text messages, the original chatbot was designed to extend his personality into a digital afterlife—as realistically as possible.

This raises the question: what happens to our digital doubles after we die? Already, platforms struggle to responsibly steward the legacy accounts of their dead users. It’s not hard to imagine that our digital doubles, once formed, will similarly persist—and pose ethical problems—beyond the grave. A double might serve as a memorial, or a way for our loved ones to continue to spend time with us, as Laurie Anderson has admitted to doing with a chatbot modeled after her late partner, Lou Reed. But it’s more likely that it will fall into the hands of malicious actors, as the grieving father Drew Crecente discovered when he came across an AI chatbot posing as his murdered teenage daughter. The difference between these scenarios will be a matter of informed consent and strictly-enforced identity protections.

Neither Lou Reed nor Crecente’s daughter, Jennifer Ann, are experiencing a true digital afterlife. Digital doubles are not an extension of consciousness, and it’s unlikely they ever will be. But in practical terms, it won’t matter whether a digital double is conscious—only that people interact with it as though it were. When Replika added safety measures and filters to its underlying GPT-3 model in early 2023, making it more difficult to engage in NSFW chat, it prompted a widespread outcry from users who had grown romantically attached to their chatbots. The Turing Test, after all, is not a test of AI sentience. It’s a test of human credulity.

Making a legacy double may be an intentional choice. The late Ryuichi Sakamoto, for example, performed an hour-long piano concert at the Shed in New York in early June 2023—a few months after his death. The hologram version of Sakamoto, recorded with the artist’s consent and participation in 2020, can play piano in perpetuity. “This virtual me will not age and will continue to play the piano for years, decades, and centuries,” Sakomoto said. “Will there be humans, then?”

THE PREDICTIVE SELF

Chip’s Dad always said there’s a combination for everything: to get what you want, all you have to do is figure out the right words, in the right order, and say them to the right person. He was the king of the cold email, back when people still wrote their own. So it’s simple, Chip thinks. He just needs to try every combination on Donna until he hits on one that works. He’ll pair Donna’s public double to a generator and run every apology in the book. Tweak the tone parameters until he lands on the right mix: humble but not pathetic. Sincere but not cutesy. Honest but not too honest. He should find her forgiveness combination by Valentine’s Day easily. Now if only the real Donna will return his calls.

Will you be happy in your new job? How will the pitch go? Could you ever win a political argument against your father-in-law? Perhaps a digital double, or several, could be useful in gaming out questions like these, by allowing people to safely workshop interactions by proxy. Such roleplaying would not, strictly speaking, be predictive, but it may serve as a form of emotional rehearsal, helping people to prepare for difficult conversations. Of course, this poses the risk of gamifying human relationships, reducing conversations to winnable transactions—and dooming us to a world of pick-up artists and salesmen.

The social app Aspect offers a glimpse into this world. Its Instagram-like feed is entirely devoid of real users. Instead, AI bots respond to comments and DMs in a chorus of generated witticisms and encouragements. Of course, “real” social media platforms are overrun with bots too. But rather than helping their users workshop social interactions—or taking the place of human interactions entirely—they serve more opaque political and commercial ends.

The digital double may prove more productive as a tool for self-knowledge. A second self is a kind of mirror, after all—and given enough personal data, that mirror could become a crystal ball. Soon, thoughtful queries to a digital double might help to identify our blind spots, cognitive biases, and latent motivations; in the years to come, the double might guide our future actions by offering predictions or suggestions on what to do next.

Of course, the usefulness of a digital double for prediction or productivity depends on its fidelity to the real thing. Nobody wants their interests represented by an unreliable, inaccurate or incomplete bot. Herein lies the trouble. AI models can only generate responses based on their training datasets—which are, by nature, archives. But how a person behaves in the future, or how they might react to a completely novel input, is rarely a linear extrapolation of their past experience. Life is funny that way. We often surprise ourselves. We are, after all, singular.