Our devices are increasingly becoming the primary medium through which we relate to one another. Modem partnered with Morgan Catalina, holistic sexuality educator, and industrial designer Maxime le Grelle to explore the tension between technology and human connection. Networked Intimacy envisions the potential of interpersonal relationships in the connected age through a series of speculative hardware interventions.

What comes to mind when you think of intimacy? What does closeness – with a friend, family member, or romantic partner – feel like? Waking up in the middle of the night and wrapping your arm around your partner, quietly trying to sync your breath to theirs? Saying goodbye to your parents at the airport, feeling, on a sharp physical level, how the distance between you gradually expands? In a department store, picking up a perfume that an ex used to wear, as the scent momentarily brings memories to the surface?

As humans, we yearn to be intimate with others. We crave touch, embraces, shared emotions and stimulating conversations. Human intimacy is deeply embodied and multi-sensory – we respond to voices, touch and scent as much as we do to visual cues. Today interpersonal intimacy is also deeply technological: enabled by smartphones, laptops, apps and video calls. Not only is a text message notification from a loved one capable of producing a dopamine hit – we are now able to have relationships (friendly, professional, romantic) which are carried out entirely online, without ever meeting face-to-face. But in our increasingly digitised reality, are we truly satisfied with the level of connection current technology is able to provide?

Both the potential and the limitations of technology-mediated interactions have become especially apparent during the onset of Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns. A large number of people were able to perform work tasks and stay in touch with their social circles and family online, but there was still a profound sense of isolation. The intimacy hunger was sharp – but even though experienced on a much broader scale than before, it was hardly new. Loneliness has been on the rise in the last decade (UK, for example, hired their minister of loneliness in 2018), and contemporary technological development looms large in the picture.

As American academic John Culkin once pointed out, “we shape our tools and, thereafter, our tools shape us,” — which certainly applies to technologies we use to connect to each other. Deeply integrated in our lifestyles, they create new opportunities and pose risks – they promise to provide ever-present connection, and yet seem to be driving us further apart.

Human intimacy today is increasingly hybrid – an intricate combination of online and offline interactions. But as we strive to achieve meaningful connections through the same devices we use to check our emails and order groceries, the question inevitably arises: is this hybridity a gain or a loss? And how do we strike a delicate balance with technology?

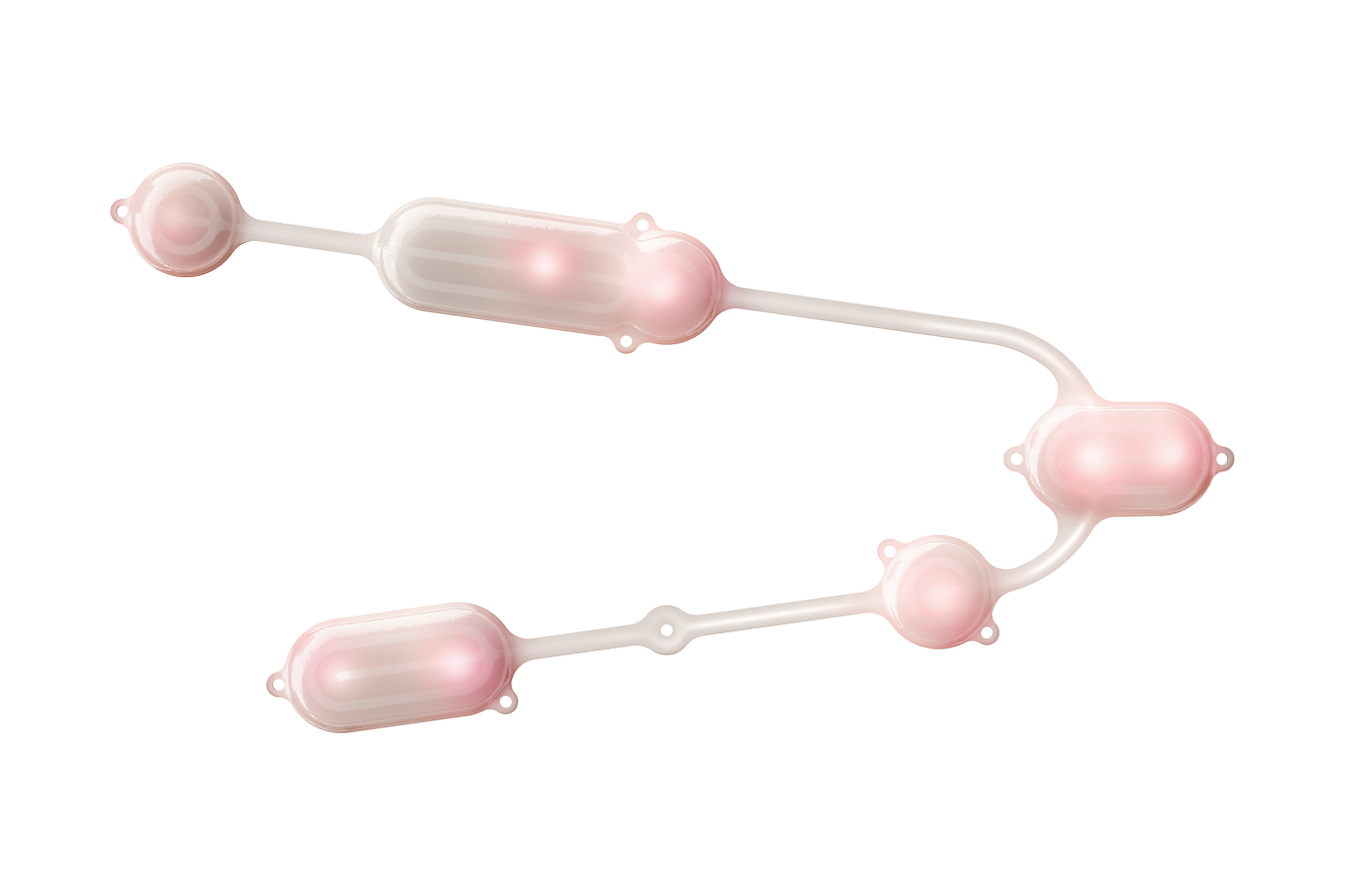

The touch patches can be adhered to various places on the skin and worn under clothing. The liquid heat fluid flowing through the patch emits the feeling of touch or greeting from a distance.

BALANCING ONLINE AND OFFLINE

In the film Army of Love by Ingo Niermann and Alexa Karolinski, we find ourselves in the calming settings of a spa. The swimming pool is radiant, and the room warm and comfortable. We observe people bathing, interacting and sharing touch. The film, produced for the 9th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art in 2016, explores intimacy, disability, queerness, beauty, and human connection. The narrative is built around real-life interviews with people musing on interpersonal intimacy – and the idea that everyone deserves touch, affection and love. Army of Love is part of a bigger eponymous project which introduces “a propositional regiment of soldiers diverse in age and appearance and tasked with solving the persistent social malaise of dire loneliness.” That is, Army of Love is there to provide affection, touch and intimacy to everyone in need – regardless of age, gender, appearance and other characteristics. This utopian proposal exposes how much we are in need of touch and connection – and how not everyone has equal access to them.

Remote online communication offers great potential for accessibility. For example, the internet enables people with disabilities to communicate effectively using communication gadgets that meet their needs. People with physical access requirements are able to participate in social life and work without having to navigate ableist environments.

Online communication also allows us to connect with like-minded people worldwide. Meaningful relationships can be fostered on Discord, Twitch, or even Minecraft or Fortnite. Second Life. We can choose a fictional avatar which transcends our actual appearance and age. We can also create a space to live out our deepest authentic selves, which is often true of LGBTQI+ people escaping discrimination in hostile IRL environments.

Online communities have an almost utopian potential, but the reality is much more complex. If having a stable internet connection solved the problem, we wouldn’t be lonely anymore – and yet loneliness remains one of the most pressing public health concerns worldwide. Technology, as enabling as it can be, poses certain challenges for mental health, wellbeing, and forming and sustaining relationships.

Author and psychology professor Michelle Drouin described what we are collectively going through as “intimacy famine” connected to decreasing opportunities for deep connection. The omnipresence of devices is a key factor – we have to effectively compete with them for each other’s attention. Mobile technology has made each of us “pausable”: face-to-face conversations are routinely interrupted by incoming calls and text messages. 89% of people admit that they interrupted their last social interaction for their phones, and 82% say that the conversation suffered from it. A 2019 study with family scientist Brandon McDaniel found that 72% of couples felt a ‘technoference’ in their relationship.

When it comes to connecting through technology, our interactions are constant and reactive. Our friendships and familial relations are a stream of notifications on various apps. Not only has research linked notifications themselves to a rise of depression and anxiety – it also creates an illusion of connection constantly available to us.

We communicate where and when we wish and disengage at will. We are more reachable than ever before and are able to connect at almost any given moment, no matter the context. The instant nature of access means that moments which previously carried emotional weight can go unnoticed: we can break up with someone on our morning bus journey to work or express our condolences whilst going through a supermarket.

As the frequency of our interactions increases, depth often suffers. Part of the problem lies in the lifestyle: multitasking, struggling to find time and capacity to focus. But the limitations of technology we use to connect also plays a part: often focused on visual cues, they make us neglect other senses and lose out on metamessages sent through tone of voice, body language and touch.

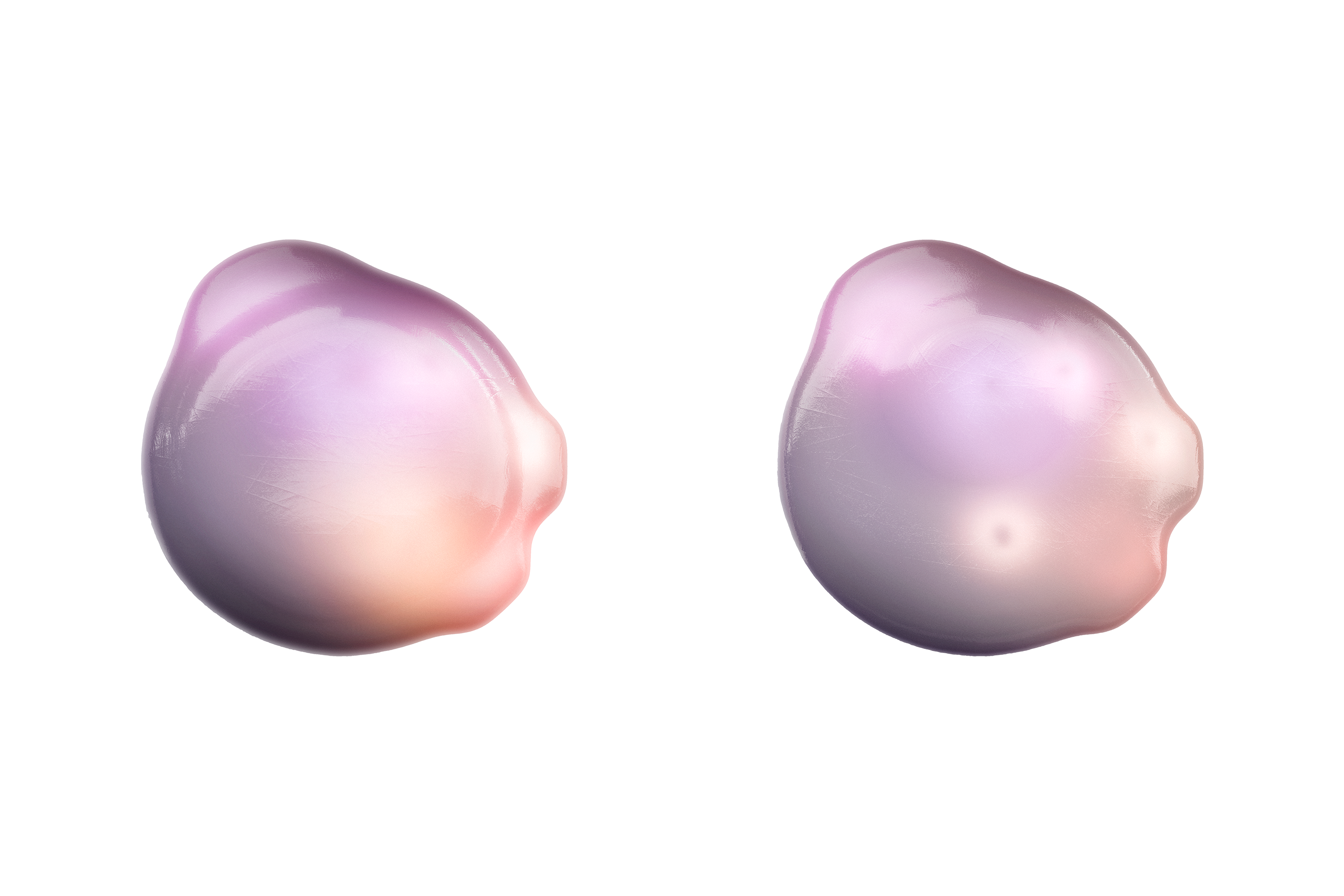

The collar releases a scent when interacting with others digitally. For the user, each unique scent is connected to a particular person and represents their intimate connection, such as the scent of their child's hair, their lover's skin or their home.

THE MEANING OF PHYSICAL TOUCH AND EMBODIED INTERACTION

Our experience of intimacy relies on multiple intertwined senses: touch, hearing, sight, smell and taste. In the last few decades, our interaction with technology has been overwhelmingly visual – yet touch remains a crucial part. Today, an average person touches their phone 2,617 per day (~ every 30 seconds). At times, this impulse is social: to respond to or send a message, or make a call. Other times, we touch our phones compulsively. Researchers actually suggest that people derive a sense of psychological comfort and stress relief from handling their smartphone. The weight of the smartphone in the hand or pocket is reassuringly familiar – we take it on walks, to bed, and to the bathroom. It is likely that we experience physical interaction with our smartphone much more frequently than with other people. A smartphone is always available – yet it doesn’t fulfill our basic need for touch; people can feel negative moods and anxiety symptoms when deprived of hugs, kisses, or acts of greeting like handshakes that the smartphone so often replaces.

Touch, however, is not limited to interpersonal connection – it is also about exploring our surroundings. Opening a glossy magazine, flicking a lightswitch, or looking through clothes on the store hangers – all these actions contribute to our holistic perception. A lot of them are also becoming obsolete, replaced by a digital experience. In “Designing for the Tactile Experience”, designer Lucia Kolesárová suggests that very different actions of buying a cinema ticket, confessing love and looking for a recipe to cook for dinner, are essentially the same action in the digital world: “I fill text fields. I hit a button.”

The increasingly digital nature of interacting with the world is undeniably practical – but it is likely to have a physical effect for the emerging generation. The density of nerve endings in our fingertips is enormous, but if we don’t use our fingers during childhood or youth development, we become “fingerblind”. Our increasingly digital behavior is actually making us feel less.

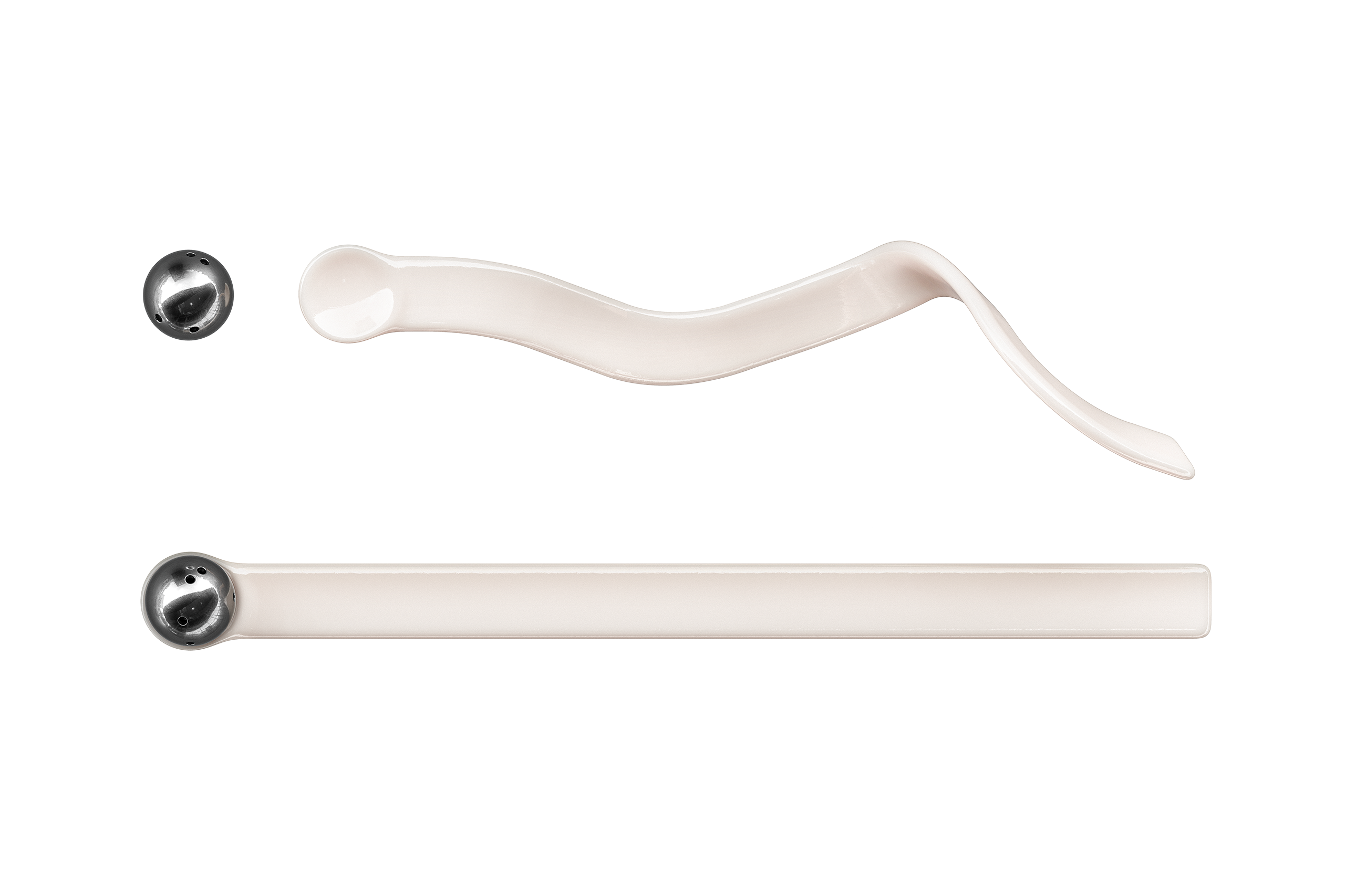

The breathing pods helps to create a digitally-triggered version of this embodied connection. The pod’s shape and light expand and decrease in sync with the person's conversational partner — through holding their respective pods, two people can synchronize their breathing and establish a focused connection.

SOLVE THE EMBODIMENT PROBLEM WITH TECHNOLOGY

Today, we are on the brink of the new era of connection enabled by the rapid development of new communication technologies. But will we be able to use all our senses to engage in this new world? While tools which would allow us not only to see but feel are coming to the market gradually, the integration of embodied experiences in our device-enabled interactions has already started.

Haptic feedback, a term used to describe ways information can be communicated through the sense of touch using science and technology, is becoming increasingly widespread. Most likely, you have experienced it already: a stylised vibration of PlayStation 5 or Meta Quest controllers, a click of MacBook touchpad, a slight shudder in your smartphone when you select a particular feature, or wake-up pulse of a smartwatch. The field of haptic engineering has existed since the 1940’s, but has been increasingly in the spotlight for the last half a decade as the application is becoming more widespread. But what are the first cases of using haptics for connecting with another human being?

In her book How to Feel: The Science and Meaning of Touch, author Sushma Subramanian describes her experience of using an experimental app to experience remote touch with her long-distance partner. “Our fingers meet up near the center of the screen, and I can feel the little raised spot, like the glass screen is a little warped. We stay there, rubbing the impression of each other’s presence,” she writes. “I let him take a few seconds to make sense of what he’s feeling and then I move my finger away. He tries to come closer again. I dart away, and he chases me. I stop and let him catch me, letting his finger linger on top of mine. We gently nuzzle them against each other. We are flirting, haptically!” What follows, when they both have to give up the devices, is the sense of withdrawal and sadness – a true marker of how powerful the experience could be.

As technology is becoming increasingly ubiquitous in the most personal aspects of our lives, intimacy should be a more prominent concern for its creators. The next decade poses a challenge of closing the intimacy gap which still exists in technology we use today. Devices for the future of human connection should be designed with intimacy in mind – not just the attention economy. After all, our true need is not becoming closer with technology, but fostering and retaining connections with other human beings. In our close-knit relationships with interpersonal intimacy tools, we have to strive not to lose sight (and touch) of each other.