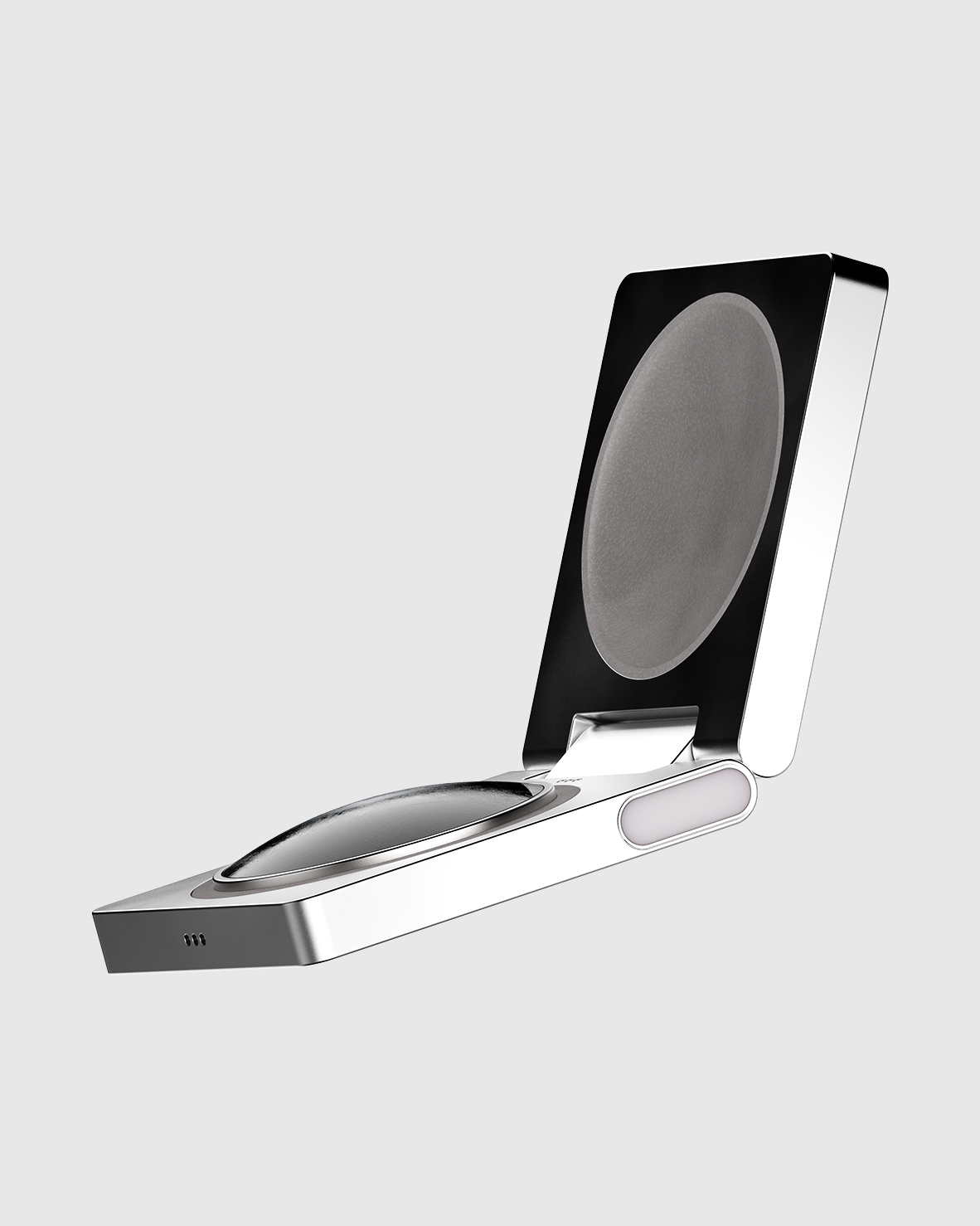

As we document our lives more than ever before, smartphones may paradoxically diminish our ability to recall these moments. Modem collaborated with industrial designer Betuel Benitez and design researcher Kotomi Tanaka from UC Berkeley to explore how spatial technologies could revolutionise our approach to memory retention and recall. Memory Machines envisions a speculative device designed to enhance our memory through the recreation of immersive 3D scenes.

Enter one of the notable depositories of human culture, like the Louvre or The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and you’ll face an intense urge to remember. Every visitor wants a small fragment of the collective heritage stored within these walls. Most will take out their phones, walking through the galleries snapping photos of Renaissance paintings, taking in the artworks through their smartphone screens. Whether these images ever get revisited doesn’t matter – the act of photographing them is a way of preserving the moment in a seemingly more permanent way than just seeing.

Today, smartphones are key to experiencing memorable events: from concerts and sports games to kids’ birthday parties, weddings and picturesque nature hikes. Our urge to photograph the memorable is, of course, nothing new: the first Kodak box camera aimed at amateur use was introduced as early as 1888. Image-making technology got cheaper and more user-friendly over the centuries, with the first point-and-shoot camera coming to the market in 1963, digital cameras taking over in the mid-to-late 1990s and the camera phone in 2000. Taking, storing and arranging photos to preserve and share our memories is a long-standing tradition, but with the introduction of smartphones, the scale has expanded dramatically.

With the inception of image-centric legacy social media, like Instagram, we often feel compelled to document our daily routines, while TikTok has made video an essential part of communication and creativity. Every day, billions of photos, snaps, and TikToks are produced. Today, the number of photos we take in a single year surpasses the total captured throughout the entire lifespan of the analogue camera industry.

One of the key reasons why digital image-capturing technology has become synonymous with memories is the ubiquity of smartphones. Mobile photography has evolved to seamlessly fit our lifestyles, reducing the friction between technology and experiencing the moment. The camera focuses and corrects exposure automatically. There are hardware shortcuts and voice commands which allow for maximum speed. Documentation has become second nature, and as a result, we increasingly use photos and video as the primary means to relive and re-engage with our memories.

OUTSOURCING MEMORY TO OUR DEVICES

The digital archive of our data, including our most valuable memories, is expanding rapidly. The growing capacity of cloud storage means that we are able to create what Douglas Coupland, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Shumon Basar described in The Extreme Self: Age Of You as “a dematerialized parallel you” stored anonymously in the cloud. Smartphones have become easily accessible and incredibly capable memory hard drives – but does this enhance or diminish our actual cognitive capacity to remember?

There is no straightforward answer. However, research suggests that taking a photo is not necessarily the best way to preserve a memory. Sometimes, we get distracted with the actual process of taking a photo, too immersed in tinkering with settings and composition to experience the moment. Another reason has to do with the broader consequences of outsourcing our memory to a device. “When people rely on technology to remember something for them, they’re essentially outsourcing their memory,” Linda Henkel, a psychology professor at Fairfield University, told NPR. “They know their camera is capturing that moment for them, so they don’t pay full attention to it in a way that might help them remember.” Specialising in research of memory and cognition across the lifespan, Henkel explored this effect of photography on recollection in a 2013 study titled “Point-and-shoot memories”. It showed that people had a harder time remembering art objects they’d seen in a museum when they took pictures of them. The study has since been replicated in 2017 and 2021.

At the same time, there are still nuances to how we take pictures. If we are intentional and focus on the details of the object or situation before we capture them, it could reinforce our memories. In the long term, photos can also serve as visual cues which prevent memories from deteriorating. But the danger of over-reliance on external devices is prevalent: if we hand over the responsibility to remember the photos and videos we take, we are less likely to preserve the moments in our minds.

AI RECALL

Memory is foundational to human existence: it allows us to create social links, form distinct identities and create principles for shared living. But in the past two decades, researchers have found that memory is not as reliable as we had previously believed – in fact, it’s incredibly fluid and malleable. No memories are static: every time we retrieve one, we change it slightly and only remember the revised version. Our biases and beliefs also play a part. ‘When we have strong expectations about how the world should be, and our memory starts fading a little bit – even after just a few seconds – we start filling in based on our expectations’, concluded Dr Marte Otten from the University of Amsterdam, author of the 2023 research paper ‘Seeing Ɔ, remembering C: Illusions in short-term memory’.

How we remember is inextricably linked to the technology we use. With the expansion of the internet, we gained access to timelines which go beyond our own memory, a continuous time warp. The effect is perfectly summed up by artist Mark Leckey while talking about his iconic 1999 video work Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, compiled of found footage from British dance floors in the previous few decades. ‘Fiorucci is essentially a ghost film…” he said. “Some people don’t enjoy Fiorucci because they’d rather keep the past as their memories, within their own bodies. It’s like a cursed video; if they see Fiorucci it overwrites their memory.”

As AI becomes widely accessible to the public, it has the potential to change how we engage with our documented memories. In 2023, Google Photos introduced “a home for your Memories that lets you easily relive, customise and share your most memorable moments.” The Memories view is organized with the help of AI to easily sieve out duplicate images, outdated screenshots and other digital clutter. It also offers a combination of automated features and manual controls: users can name their memories, include hints for especially meaningful details, organise scrapbook-style views or remove memories altogether. Throughout, Google is especially adamant that it is about memories, not photos.

AI has become one of the key technologies powering the way we navigate imagery. We witnessed how computer vision went from vaguely being able to identify a dog or a sunset to accurately sorting images of particular people, situations and even moods. As it improves its capacity to grasp complex relationships and contexts in images, it will be able to assist us in retrieving memories from expansive data sets. OpenAI’s GPT-4, for instance, is capable of picking up on relationships between objects in the image, undertones of humour, and even interpreting memes – abilities which could become foundational for assisting us in effortlessly surfing through personal archives.

In the not so distant future, our AI-powered devices could be able to effortlessly retrieve memories for us at any point – or at least provide apt and intuitive memory cues. It is highly intentional that the current technological narrative, like Google’s ‘Home for all your Memories’, blurs the boundaries between memories and documentation, as the outsourced memory industry picks up the pace. But while documentation is static, our human, analogue memory remains much more fluid, malleable and linked to the intricacies of our lived emotional experience. The analogue process of remembering is a crucial part of why memory remains a cultural fixture, from Andrei Tarkovsky’s ‘Mirror’ to Philip K Dick’s ‘Minority Report’ to Hollywood blockbusters like ‘Total Recall’. Not only does the process of recalling a memory reinforce its imprint, it also gives us the agency of shaping our own narrative, even if by default as unreliable narrators. As the AI optimisation of personal archives grows, we will have to re-evaluate what this raw, flawed recall means for us as individuals and as a society.

IMMERSIVE RECOLLECTIONS

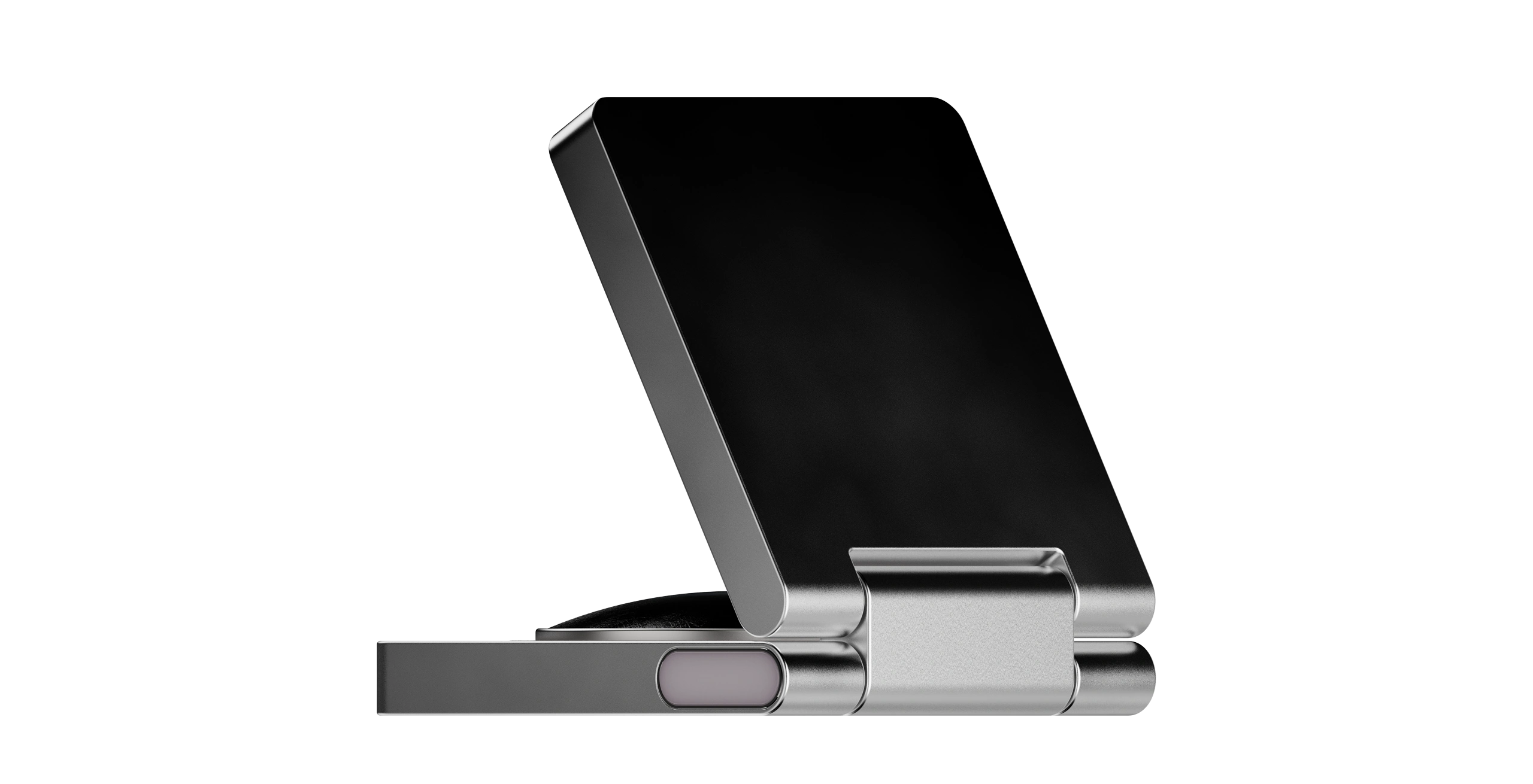

Over the last decade, smartphone cameras have evolved tremendously, both on the hardware and software side. Today our ability to take better photos does not only depend on a better lens and zoom capacity, but the AI and machine learning algorithms powering computational photography. The introduction of spatial computing could be the next step in creating more immersive – and similarly AI-powered – images and videos.

With the launch of Apple Vision Pro in 2023, Apple unveiled spatial photos, offering a 3D approach to capturing memories. According to the presentation, these spatial videos and photos possess “incredible depth”. An early user of this feature described his experience as ethereal: “The playback of the videos happens in what seems like a hazy, light, borderless frame, giving the videos a dreamlike quality. It is a very strange feeling — as if you have been transported back in time — and the videos have a dimensionality to them. The spatial videos I experienced felt more like memories — somewhere between reality and an abstraction of it.” The newly released iPhone 15 Pro includes a new lens system that allows people to record spatial videos. In the Apple Vision Pro presentation, we see a dad smiling at the videos of his daughters displayed in the room through the headset – backing up Apple’s promises of being able “to relive a memory as if you’re right back in the moment”.

Moving from 2D images to immersive 3D scenes is one of the key shifts in the relationship between documentation and memory. To step inside a scene from the past, we wouldn’t need radically new devices – we already have the technical capacity to do so. Created in 2020, neural radiance fields (NeRFs) offer a glimpse of how we could dynamically navigate a previously captured scene. With the help of NeRFs, 2D images can be turned into 3D photorealistic scenes with an impressive range of textures and details. The technology is enabled by a neural network that can accurately represent what each pixel’s colour looks like depending on the viewing angle (otherwise known as the radiance). After it’s compiled, it can be used to render new views of the object or scene from any viewpoint.

3D Gaussian Splatting is another technique that allows real-time rendering of photorealistic scenes trained on a small sample of images. While NeRF is a deep learning-based technique, Gaussian splatting is a traditional method used for volume rendering, often applied in contexts like medical imaging and scientific visualization. Working in different ways, both allow the transformation of 2D imagery into interactive 3D scenes.

Letting go of a fixed viewpoint is crucial to the experience of these immersive recollections. Imagine looking at a photograph of a place you only vaguely remember – perhaps a room from your past. In the 3D recollection, you will no longer be bound to the photographer’s point of view: you could come closer to a certain object, turn around, and glance over the small details which could have seemed insignificant at the time but are crucial for the process of remembering. NeRFs and 3D Gaussian Splatting could be foundational to creating memory devices of the future, capable of capturing and recreating immersive and interactive scenes with fluid viewpoints. One capture could hold an extensive number of memory cues, both intentional and unintentional.

In his account of using NeRF, Michael Rubloff, founder of Neural Radiance Fields and Radiant, wrote about exploring his former partner’s apartment: “While walking around the scene, the most moving part of it was not the subject but rather a pair of my socks on the floor. At once, all the times of her pleading with me to pick up my socks came back, and I was reminded of a time completely forgotten.” The pair of socks could have been easily left out of the photo, and yet they resurfaced – and the complex memories and emotions resurfaced with them. It highlights how certain aspects of it will always be malleable, unpredictable and flawed.

As memory continues to be interlinked with technology, its very meaning is likely to shift in the next decade. As we continue to document more of our lives than ever before, digital recollection will become more commonplace, and AI-powered navigation of our personal archives more intuitive. At the same time, outsourcing memory to our devices has the potential to threaten our cognitive capabilities to recall and revisit memorable moments. We will witness the new delicate balance emerge between the deeply human process behind the way we remember and the new wave of immersive technologies tasked with connecting us to our past – and ourselves.