By entangling digital and physical worlds, Augmented Reality is about to fundamentally change the ways in which we experience our cities. Modem partnered with Pablo Castillo Luna, architect and researcher at Harvard Graduate School of Design, to explore the relationship between AR and the future of architecture. The Augmented City presents a manifesto for addressing the vast promises and implications of this new mediated urban reality.

In a brilliant paragraph-long story written in the 1940s, the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges describes the perfect map. Furnished with every imaginable detail, the map was virtually indistinguishable from the territory it represented. But its precision was exactly what made it useless: the map was the same size as the place it depicted and took just as long to navigate.

Until recently, maps served as a condensed model of the world; they represented only the essential details of a place to function as a wayfinding device. With the invention of geospatial technologies—systems that glean and stitch together satellite, aerial, and ground-level imagery of the world, such as GPS—digital maps have become closer mirrors to the physical world. Featuring Borgesian-level scale and detail, these maps offer additional information layers that help us navigate even the most complex urban environment, all from a mobile device that fits neatly in our pockets. But what if a digital map could serve not just as a mirror of a city, but as an extension of it? What if this augmented layer could generate new social experiences, prototype speculative urban developments for citizens to interact with, or serve as a portal to a city’s past and possible futures?

Current advances in geospatial technologies are rapidly ushering in an expanded urban experience with Augmented Reality (AR). Unlike the black box of Virtual Reality (VR), which requires an insular headset that closes down the user’s connection to the physical world, AR enhances it. It does this by overlaying a digital layer of visual, auditory, or sensory information onto the physical world in real-time, offering a wide range of applications: from locating rideshares and enhancing navigation, to improving public safety and strengthening local communities. Using unprecedented mapping technology and breakthrough virtual positioning systems, this digital layer will feel as dynamic and interactive as the physical world. As founding editor of Wired Magazine Kevin Kelly suggests, this future interface will imbue virtual space with a sense of “placeness” for the first time; here, “a virtual building will have volume, a virtual chair will exhibit chairness, and a virtual street will have layers of textures, gaps, and intrusions that all convey a sense of “street.”’

Although it’s only recently entered the mainstream, AR was first conceived in the 1960s by computer scientist Ivan Sutherland, who invented a head-mounted system so heavy it had to be suspended from the ceiling in order to be worn. While it’s been used in commercial contexts since 2008, AR first captured public attention with the uproarious launch of Pokémon GO in 2016, which saw players falling off cliffs and getting held for ransom in their attempts to catch the digital monsters, trackable via their phone cameras and GPS coordinates. Entertainment may be the most immediate connotation most of us have with AR at present, but the technology offers an incredible array of potential uses and future applications within architecture and urbanism writ large.

Many cities around the world – from Buffalo, Arizona to the city-state of Andorra – have already launched AR-based initiatives to improve urban life across sectors. Last year, the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy launched an AR experience that enables visitors to the access the city’s cluster of Frederick Law Olmsted-designed green spaces in a new light. Overlaying location-specific 3D models of demolished historical landmarks and gardens, visitors can look back on the parks’ rich architectural history and understand the importance of preserving its present-day ecosystem. Later this year, the city of Charlotte in North Carolina will launch an ambitious AR project that renders visible the historically Black neighborhoods of the city that were razed in the 1960s, bringing to light the spatial legacies of systemic racism enacted by urban renewal projects.

On a larger scale, the MIT Media Lab teamed up with the nation of Andorra to develop CityScope, an AR-based urban planning and development platform that allows Andorra’s 77,000 citizens to view and comment upon planning proposals and potential tech interventions like self-driving cars, facilitating civic engagement and future collective decision-making. Users can also upload live information about traffic, energy consumption, and geotag their favorite parts of the city, offering useful insights on how the urban environment is experienced that could feed into further urban planning.

New advances in geospatial imaging and the sheer number of patents filed for AR wearables indicate that the industry will soon experience a flood of new products entering the market. With the arrival of open-access AR developer platforms such as Google’s ARCore Geospatial API, new uses of this technology will emerge across disciplines. Launched in May 2022, the Geospatial API is a game-changer for location-based AR applications, as it offers developers precise, real-time position and orientation services powered by Visual Positioning Service (VPS). Prior to its official launch, Google granted a number of tech companies like Lyft and Unity early access to the API. This has resulted in already-felt improvements to Lyft’s commercial rideshare services, as well as the development of interactive, site-specific AR experiences such as Pocketgarden, powered by Unity, which allows users to cultivate virtual gardens anywhere in the world.

As these types of technologies are adopted by independent developers, artists, architects, and urbanists, we will see new applications of AR urbanism as well as the proliferation of alternative forms of communication and countercultural spaces. This will also bring in productive frictions and critical thinking around who gets to control these spaces and whom exactly they serve – as seen in the virtual “graffiti-bombing” of Snapchat’s and Jeff Koons’ collaborative AR sculpture from 2017.

AR ARCHITECTURE: TOWARDS A NEW AESTHETIC PROTOCOL

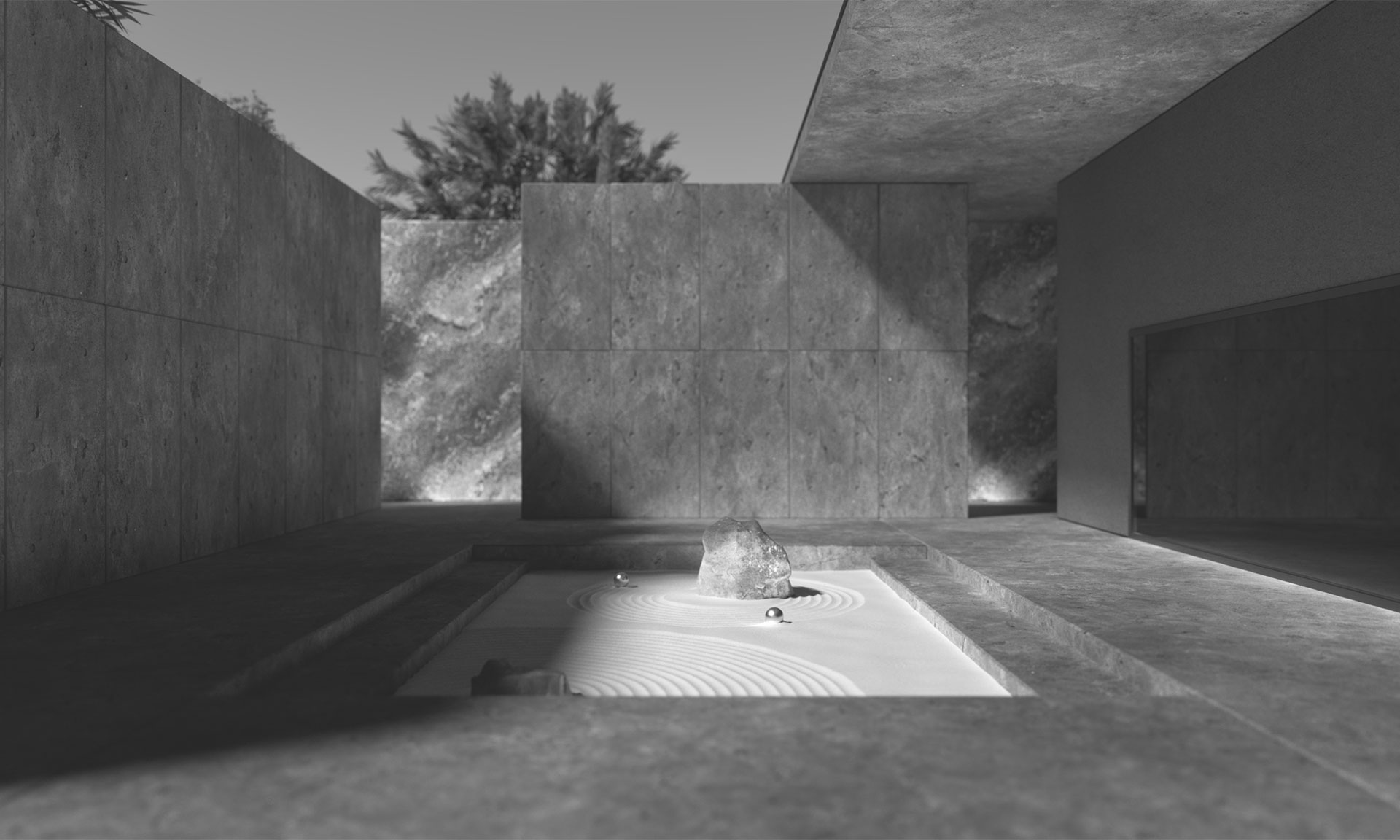

In addition to AR’s capacity to transform the design and experience of cities, its impact on architecture will be equally as significant. It has already had a sizeable influence on the construction and engineering industries, with applications such as GAMMA AR offering a safer and more efficient building environment for construction workers. Although a clear architectural style has yet to emerge from AR applications, new paradigms in architecture have historically been catalyzed by technological advances. This can be seen from the impact of reinforced concrete upon modernism’s ideologies, as expressed in Le Corbusier’s Five Points of New Architecture, to the automobile-triggered urban sprawl, which informed the postmodern lexicon of Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi’s Learning from Las Vegas, and more recently in the undulating swirls of Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry’s parametric design, which found its voice through 3D modeling.

What aesthetic considerations might concern AR architecture? In a prescient essay from 2005 titled The Poetics of Augmented Space, writer, artist, and researcher Lev Manovich argues that the aesthetic design challenge of augmented architecture is not a particularly new one. AR buildings are essentially a pastiche: their facades will act as data layers upon which many other buildings and narratives are superimposed. Manovich takes the extreme “brandscaping” example of the OMA / Rem Koolhaas’ Prada store in New York from 2002, which featured gigantic monitors that advertised both the products on sale alongside data that forms Prada’s marketing decisions – effectively unveiling the operating logic of the company. Manovich argues that the electronic screen surface does not need to default as an extra layer of advertising; it can have a potent political and social function if cultural actors including architects “consider the ‘invisible’ space of electronic data flows as substance, rather than just as void.”

When designing augmented architecture – which is to say buildings that exist across both physical and digital environments – new material conditions will need to be taken into account. For instance, glass and other transparent building materials routinely throw off geospatial sensors, and harsh glares from reflective surfaces are not conducive to the camera interface of many AR tools. The future aesthetic of AR architecture will run counter to the modern glass towers that have come to dominate global cities—which, in addition to being an oppressive, homogeneous building typology, are unsustainable for both their energy consumption and the threat they pose to local ecologies.

AR architecture would be well suited to higher degrees of localization, wherein the building becomes a canvas for local, site-specific design interventions. As Manovich suggests, these buildings could also become signifiers of the technological processes they facilitate—for instance, a building that’s become a popular pinned location for AR content within a city could feature an indicator of its augmented application on its physical facade, akin to a high-score chart on a video game’s loading screen. By encouraging localization in both its material presence in the physical world and the mediated interactions it enables in digital space, AR architecture has the capacity to become a more accessible design protocol that expresses localized architectural styles, its own interactivity, and its future applications.

The Italian design collective Superstudio’s speculative project Continuous Monument (1965) serves as a welcome warning here. As a tongue-in-cheek critique of a homogenized global architecture, the project also meditated on the ambivalent relationship between nature and architecture, and the increasingly blurred boundaries between humans and technology. It asks, how do these changing ideas of architecture, urbanism, and (virtual) space change us, their users, in turn? As a type of architecture that is poised between physical and digital spaces, and that offers both agency and possibility in both realms, AR architecture will influence the material and spatial qualities of IRL architecture while expanding the possibilities of the discipline.

THE FUTURE OF AR CITIES

Cities for Cyborgs, a critical design project conceived in 2010 by the designer and filmmaker Keiichi Matsuda, introduces a mini-rulebook of ten entries for designing the future city (these include multiple warnings for architects: “don’t be boring” and “understand mediation”). In his guidebook, Matsuda introduces the “CY-2010” cyborg—which is to say the modern-day human—as a creature that is rapidly reshaped by its technologies, including its creation of hybrid physical-virtual space, and is tasked with the radical reshaping of its urban environment in order for it to flourish. “This is the challenge that the city is facing now,” explains Matsuda. “It can be an exciting, inspirational and joyful space that enriches and supports life, but it is up to us, the CY-2010, to make it a reality.”

Going beyond the flattened 2D map of Borges’ time, and the abstract 3D representation of the world offered by more recent GPS technologies, AR will fundamentally alter our understanding of space and the urban environment. This hybrid digital-physical space will become a 4D technology: a sensing layer of its own that allows us to toggle forward and back in time, readily collapsing distances and borders between its users and radically reshaping our experience of the augmented city.

With the popularization of AR technologies, new forms of collaborative urban design, civic engagement, and creative expression through architecture will be possible. With the simultaneous introduction of new decentralized operating platforms afforded by blockchain and the premise of Web3, it will also be possible to access and utilize this technology with more agency and transparency than before. The incoming shift into augmented urbanism is an opportunity to reconsider not just the role of architecture, but also the future role of the city and its implications. Building on this research, we propose a manifesto for addressing the future conditions of augmented urbanism.

The Augmented City: A Manifesto

THE DEMOCRATIZATION OF ARCHITECTURE

Visionary architects have a tradition of imagining the cities of the future. Broadacre City by Frank Lloyd Wright, Highrise City by Hilberseimer, Radiant City by Le Corbusier, and Supersurface by Superstudio are paradigmatic examples of how our ways of living are shaped by the spatial configuration of our environment. In a world where AR is ubiquitous, spatial design will be practiced and broadcasted by anybody so inclined. Architecture will merge with filmmaking, game design, and programming to become an experiential form of new media. Users will adapt the city to their needs instead of adapting themselves to the city. Architects, in turn, will become mediators between the physical and digital realms.

URBAN HYPER-CUSTOMIZATION

Personal interactions in the virtual realm in Web 1 and Web 2 challenged the role of public spaces as the main catalyzers of social exchange. In contrast to exclusively digital social spheres, the augmented city will allow the creation of site-specific, custom, shared experiences that will enhance the interactions between users and their surroundings. Location-based AR entertainment such as games, events, and movies will be customized to respond to geo-specific real-world locations, reshaping the mixed-reality urban environment as an active part of social life.

EVER-EVOLVING ENVIRONMENTS

In Learning From Las Vegas, Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi defined ‘decorated sheds’ as places where ornament was independent from the spatial and structural aspects of a building. Likewise, the augmented city could be reduced to a canvas to be populated with digital projections that are unrelated to its physical space. However, AR does not only add, but also allows to distort or modify three-dimensional information extracted from physical environments. Architecture will no longer be about construction, but about spatial modification. While buildings will continue to be static and passive, the augmented built environment will be a fluid and ever-evolving space.

MACHINE-READABLE MATERIALS

Augmented reality technologies require both a geometric and semantic understanding of reality in order to transpose information across the physical and digital worlds. However, certain material properties like reflectiveness and transparency are not easily interpreted by sensors and cameras. If the medium through which architecture is perceived affects the possibilities of architectural output, augmented space will inevitably develop a new aesthetic. Just as the car changed the symbolic expression of architecture to be read and understood at a higher speed, the ubiquity of AR will dictate the choice of building materials for the city to be readable and understandable for humans and machines alike.

GEO-SEMANTIC MIRROR OF REALITY

The contemporary city is more than its physical layer; it is a collage of data, reviews, and other information, yet the physical world as we know it shows only one of these many layers. The development and rapid improvement of global localization technologies allow, for the first time, these additional information layers to be visualized, analyzed, and experienced spatially. As a result, the augmented city will require a continually updated mapping of the ever-changing physical world. With the mass introduction of Virtual Positioning Systems (VPS) technologies within wearable AR headsets, the very act of perceiving the world will be a remapping of it. The experience of the augmented world and the mapping of the physical world will occur simultaneously, creating an unprecedented equivalency between production and consumption.

LOCATION-BASED DIGITAL PROTOCOLS

Architects and urban planners have traditionally used zoning as a method to define, shape, and regulate the urban environment. In the augmented city, these regulations will be dictated and implemented digitally. For instance, geo-fencing sets virtual boundaries around geographical locations, triggering certain machine behaviors in particular physical areas. In augmented urbanism, regulating and planning will progressively shift from governments to a broader range of stakeholders with digital agency, including tech companies and developers. The future augmented city will not be defined by drawings and regulations but through geo-specific digital protocols.

The introduction of augmented reality into architecture and urbanism will fundamentally alter the ways in which we design and experience cities. Through its integration of the digital and physical realms, this technology opens up new opportunities for collaborative and creative urban design protocols, while promoting a deeper understanding of the influence that a city’s past wields upon its future. As an extra “sensing layer” for the urban commons, AR also raises important questions around the ownership and privatization of virtual space. While these questions are yet to be answered, it’s clear that augmented urbanism will offer new paradigms for an ever-evolving, location-specific, and collaborative approach to urbanism and architecture. The augmented city of the future is coming; it’s up to us, its users, to make its vast creative, cultural, and political potentials a reality.

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe to the Modem newsletter to receive early access to our latest research papers exploring new and emerging futures.