Autonomous driving is set to transform the car as we know it. Modem partnered with female-led design studio DADA Projects and Jinghan Wu, landscape architect at Harvard Graduate School of Design, to explore what the car might become when humans are no longer behind the wheel. The Windowless Car imagines a new kind of in-vehicle experience, focused on riding rather than driving.

Contrary to expectations of an abrupt disruption, autonomous driving is appearing gradually and steadily in everyday life, proceeding thus far along the familiar pathways established by human-operated automobiles. Today, partially automated cars share the roads with their traditional counterparts, relying upon the same infrastructure and similar vehicle designs. The surreal sensation of riding in a Waymo robotaxi for the first time, however, provides a striking reminder that the age of autonomy has barely yet begun, and that our focus on the timing of its arrival may distract us from understanding the scope and nature of its eventual impact.

Autonomous driving has the potential to once again reshape a world that was already reshaped by earlier versions of the car, affecting where we choose to live and work, how much time we are willing to spend traveling, and how we use that time in transit. Although the technology has been slow to arrive, disappointing those who have eagerly anticipated a sudden driverless revolution, it has indeed begun to change driving, in incremental stages rather than all at once. The rollout of autonomous vehicles (AVs) has not been entirely smooth, beset by glitches and operational hiccups such as errant honking. But as these growing pains are overcome, AVs will proliferate, becoming more familiar and more user-friendly. The question, then, is not so much when the technology will arrive as where it will take hold and what it will look like when it does.

As autonomous driving becomes commonplace, it will likely call into question many fundamental aspects of driving: the design of cars themselves, the roads on which they travel, the passenger experience, and the second- and third-order effects that follow from those core elements. This could represent a significant departure from driving as we have known it. “New technologies may ultimately evolve far beyond machines ‘automating’ the recognizably human task of driving,” designer Chenoe Hart writes. “Rather than robot drivers piloting cars that humans might otherwise be driving, these new technologies may transport us in an entirely different way that dispenses with accommodating human capabilities.”

In other words, our deep familiarity with the human-operated car constrains our ability to imagine what might be different when humans no longer do the driving. AVs will likely assume entirely new forms, with traditional components such as forward-facing seats, manual steering wheels – and even windows – becoming superfluous or unnecessary. At the same time, a variety of countervailing forces, from existing infrastructure to consumer preferences, will limit the car’s ability to transform completely overnight.

LEARNING FROM LAS VEGAS

To better anticipate the second- and third-order effects that autonomous driving will produce, the history of the car’s influence on the built environment is a useful guide. A century ago, the automobile was still a relatively new technology, but its transformative potential was already apparent to visionary thinkers like the architect Le Corbusier, who predicted in his 1929 book The City of Tomorrow and Its Planning that the car would overturn all traditional notions of urban planning. He was correct, of course, although the specific details of that phase change would prove harder to predict.

Several decades later, a new car-oriented landscape had coalesced for architects to observe and study. In 1972, the architects Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour published Learning from Las Vegas, which recognized the billboard-lined commercial strip as a strange new kind of physical space – the eventual product of widespread car adoption. The authors described the Las Vegas Strip as a linear city that in many ways fulfilled Le Corbusier’s prediction: a city whose planning was heavily influenced by the car and its requirements.

The Las Vegas Strip, the authors wrote, was an exaggerated version of commercial strips that had appeared all over the United States. This new environment turned itself toward the car in a literal sense. Its massive billboards and neon signs, visible from far away and perpendicular to the roadway so motorists could see them, were made for a “new landscape of big spaces, high speeds, and complex programs,” in contrast to the pedestrian-scaled Main Street that the commercial strip was superseding. Discussing the evolution of roadway signage, they wrote, “A driver 30 years ago could maintain a sense of orientation in space…But (today) the driver has no time to ponder paradoxical subtleties within a dangerous, sinuous maze. He or she relies on signs for guidance – enormous signs in vast spaces at high speeds.” In this sense, automobile travel had actually detached passengers from their physical environment, immersing them in an expanse of pure information transmitted by massive billboards that seemed to float in space.

Prescient as he was, Le Corbusier did not predict the billboard. A contemporary Le Corbusier would face a similar challenge to that of a century ago: How to predict the forms that will follow from the rise of widespread autonomous driving? “A good science fiction story should be able to predict not the automobile but the traffic jam,” said author Frederik Pohl. At present, it is more straightforward to grasp the technical realities of autonomous driving technology than the future world that will arise from its broad adoption. Ironically, the landscape of billboard advertising, which cars originally fostered, might itself become obsolete, with no human drivers looking ahead through their windshields to see those ads.

As Learning from Las Vegas attests, the visible future can lag the technology that enables it by decades. The physical infrastructure that supports driving – roads, parking lots, signage, and points of contact with overlapping systems like pedestrian rights-of-way – is inherently slow to adapt, expensive to retrofit, and often managed by multiple public and private stakeholders. Because the car is a consumer product, moreover, the radical change that autonomy represents must be made familiar and inviting in order to market it to a more cautious customer base. Early iterations of the AV might thus resemble traditional cars more closely than their operational needs dictate.

The short-term and long-term future of the AV, in other words, could be two quite different things. In the short run, it will be a dialectic between the car’s past and its future, in which the new and the familiar intermingle. In the long run, however, almost everything about the car as we know it could be different.

THE AUTONOMOUS REVOLUTION

Certain kinds of AV travel will likely gain traction before others, due to the incremental nature of the technology’s adoption. Driving automation is not a binary state but is divided into five stages or levels. Level 1, requiring the human driver’s assistance, is already becoming common; Levels 2 and 3 are degrees of partial automation that still depend upon limited human participation, with drivers monitoring and intervening as needed. Level 4 involves full automation in most conditions – often within a limited, geofenced area – and Level 5 extends full automation to all circumstances, without restrictions. Here, the robotaxis depicted in science fiction become a reality, as mentioned above. Waymo already operates such vehicles in select cities, while Tesla has announced its own Cybercab and Robovan.

The ongoing adoption of autonomous driving has an uncertain timeline, but the phased nature of the technology’s implementation raises a different question: Where might it gain an early foothold before spreading to accommodate a broader range of uses?

Longer-distance intercity travel is likely to be one such foothold, with highways providing a favorable setting for fully autonomous driving. The possibility of dedicated AV lanes on highways means that not all vehicles using those roads need to be autonomous – an arrangement that is especially helpful in the near term when AV adoption is lower. China has already built a 100-kilometer highway between Beijing and the Xiongan New Area with multiple dedicated AV lanes. Passenger preferences already seem aligned with this: A 2009 travel survey that simulated AV adoption found that, for trips shorter than 500 miles, they are competitive with both air travel and personal vehicle usage, diverting passengers equally from both modes due to factors including flexibility, convenience, and lower perceived cost.

The image of dedicated AV lanes on highways filled with long-distance travelers suggests a kind of transportation behavior, native to this emergent technology: a new mode of intercity travel. It also implies new forms for the car itself.

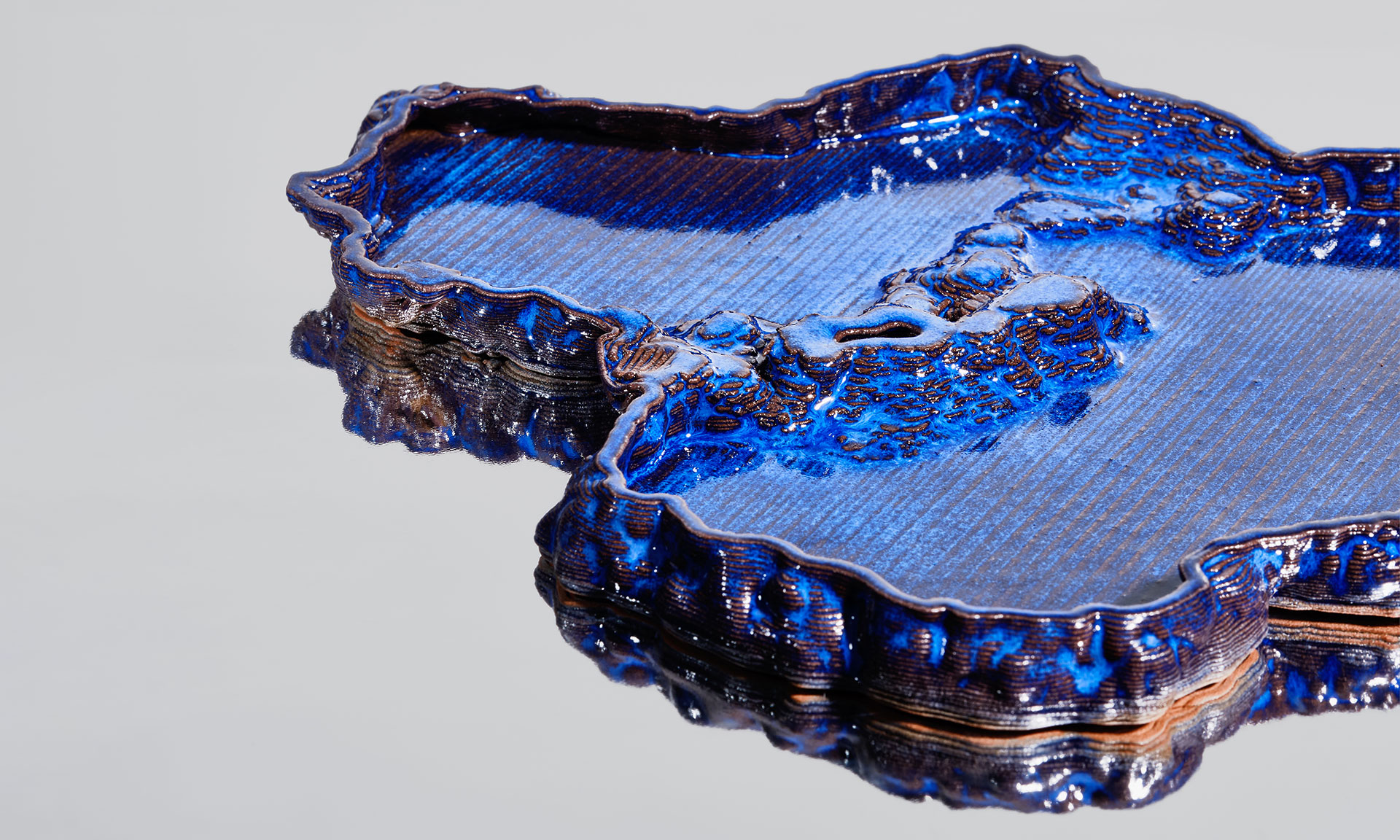

THE WINDOWLESS CAR

The rise of fully autonomous driving offers an unprecedented opportunity to redesign the car as well as the driving experience. The prospect of intercity passenger travel by AV suggests a new type of vehicle better suited for such travel – one that would probably look and feel quite different from the cars that fill the roads today. When the driver becomes the passenger, this eliminates a major constraint upon the car’s design as well as the experience of riding in it, creating a wide range of possibilities for new approaches. “Once designers of automated vehicles are no longer bound by the outdated limitations of accommodating either internal combustion technology or human operators,” Chenoe Hart writes, “they could move far beyond our present-day intuitions of what a car should look like.”

The parameters that determine the car’s present form have undergone few (if any) changes as significant as autonomy. Peter Wayner describes how car models have remained fairly consistent over the past 80 years, with “four wheels, two headlights, and windows, plenty of big, clear windows ringing the car.” AVs will upend so many design variables, he writes, that “designers can begin again with a clean file in their design software.”

With no need for a human driver to monitor the road in front of them, a major element of the traditional car could become unnecessary: windows. Lacking any operational purpose under autonomy, a car’s windows become largely detrimental. Windows make cars less safe, with glass providing less protection to passengers in an accident than a more solid exterior would. Windows also offer less privacy and poor insulation, while negatively impacting the car’s aerodynamics when they are opened.

The removal of windows as a design constraint unlocks a new set of possibilities for what AVs might look like and how it feels to ride in them. As Wayner writes, however, “The first robot cars will almost certainly have (windows) because it’s never good to ask people to endure too many radical changes.” Windows, or something that simulates them, might still serve a purpose in AVs despite their drawbacks, helping passengers to orient themselves or even feel a sense of control as they travel.

Without human drivers, the function that windows have traditionally served can be fulfilled in alternate ways – via camera systems and screens. Swedish automaker Polestar has already developed an electric SUV that does away with the rear window, replacing it with a roof-mounted rear camera that provides a more reliable image than a rear-view mirror would. This ongoing replacement of car windows with cameras, combined with advances in autonomous driving technology, suggests that those windows may be increasingly unnecessary.

The windowless car concept simply extrapolates this logic to its end point: something like an Apple Vision Pro on wheels. Released in 2024, the Apple Vision Pro demonstrated a state-of-the-art capacity to realistically simulate the user’s physical surroundings via a headset camera system, augmenting those surroundings digitally in real time. A windowless car, likewise, could simulate windows by capturing its surroundings with cameras and then displaying that imagery on in-vehicle screens, enhancing or modifying it in real time to any degree the passenger desires. This technology has the added potential to prevent motion sickness by displaying virtual content as a fixed object in the car’s external environment, better aligning the passenger’s field of view with their bodily sensation of motion.

An AV incorporating this technology in lieu of windows would respond well to the requirements of long-distance intercity travel, which autonomous driving would likely encourage. When everyone is a passenger and no one is a driver, this kind of car travel will become more like air or train travel, but with all the comfort and privacy of a personal vehicle. The best AV designs will embrace the opportunity to enhance the in-vehicle user experience, facilitating activities ranging from gaming to work to sleep and other forms of wellness. The mixed-reality view provided by window-simulating screens is one potent way to make such long trips more interesting and more interactive: The car’s outside environment could be enhanced via augmented reality or transformed in real time using generative AI.

If windowless cars replace their visual exteriors with camera-based feeds, another question immediately follows: Why depict the actual exterior environment at all? The screens that replace an AV’s windows could use immersive virtual reality to simulate any imaginable exterior – mountainous terrain, a coastal drive, or a fantasy landscape. The same technology could also use the car’s motion to simulate entirely different driving experiences.

The windowless car has the potential to enhance the process of driving, turning a routine commute into an engaging form of immersive entertainment or education that enchants our surrounding environment and helps us experience it in new ways. If we don’t need windows in cars we’ll still likely want to look out of them, even if what we’re seeing is digitally generated. In contrast to the prior era of driving, however, there is one thing we probably won’t see when we gaze out of these virtual windows: billboards. To assume otherwise would be to let the car’s past limit our imagination.

NEWSLETTER

Subscribe to the Modem newsletter to receive early access to our latest research papers exploring new and emerging futures.